Turangi Township and the Waitangi Tribunal's Binding Powers

It is a little known fact that, under certain circumstances, the Waitangi Tribunal is able to make binding recommendations. Although the Tribunal has had this power for nearly a quarter century, only once has it so far opted to exercise this option. So what were the circumstances in which it did so? Here, we look back briefly at the history of the Turangi claim.

In the 1950s the Crown drew up proposals for what at the time was the largest hydro-electric development in New Zealand. The Tongariro Power Development scheme would require a large work force and therefore accommodation for the construction workers for the many years it would take to complete the project. In 1964, following some discussion with its Ngati Turangitukua owners, Turangi was chosen as the site for a new township for these purposes.

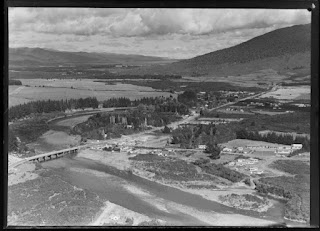

Turangi 1964 (WA-61680-G, ATL)

Ngati Turangitukua had agreed to the proposals in principle on the basis of various undertakings and assurances received from the government. These included undertakings that land required for industrial purposes would be leased for a period of 10-12 years and then be returned to the owners, and assurances that the total area required for the township would be no more than about 1000 acres. In the event, some 1665 acres was acquired by the Crown, mostly compulsorily under the provisions of the Public Works Act and the Turangi Township Act of 1964. This included the industrial area the government had undertaken only to lease.

Bulldozers were sent into to the area within days of the final Cabinet go-ahead for the project and even before the land-takings had been legally proclaimed. The next two years were traumatic ones for Ngati Turangitukua as their land was levelled and a new township was formed almost literally under their feet. Wahi tapu (sacred places) were desecrated or obliterated and the concerns of the tangata whenua completely ignored.

Following completion of the construction project in the 1970s the Crown began to sell off many of the lands it had compulsorily acquired from Ngati Turangitukua. Yet the tribe was not given the first right of purchase of these properties or provided with any assistance to re-establish an economic base for themselves. In 1990 Ngati Turangitukua filed a claim with the Waitangi Tribunal in respect of their grievances concerning the township. The Tribunal’s report, which was released in 1995, recorded 13 separate breaches of the Treaty of Waitangi in the Crown’s dealings with Turangi Maori, including the ‘draconian’ means by which Ngati Turangitukua’s lands had been taken and its failure to act fairly and honourably in its dealings with the hapu.

Ngati Turangitukua and the Crown entered negotiations following the release of the Tribunal’s report. However, these subsequently stalled over the size of any settlement package. While Maori sought the return of properties valued at $6.3 million, the Crown offered considerably less. Many of the properties sold had memorials on their titles which provided for ownership of these to be resumed by the Crown in the event that they were required for the purposes of Treaty settlements. This provision had been introduced in 1988, following a Court of Appeal decision the previous year in favour of the New Zealand Maori Council, which had been concerned that the disposal of ‘surplus’ Crown assets would diminish the potential resources available to successful Treaty claimants.

In most instances the Waitangi Tribunal could only make recommendations to the government, which it was free to accept or reject as it saw fit. But following the 1988 legislation the Tribunal could make ‘binding recommendations’, effectively ordering the compulsory return of memorialised lands (a similar provision was introduced in 1989 in respect of commercial Crown forests).

Following the breakdown in negotiations, Ngati Turangitukua returned to the Tribunal, which in 1998 issued its first (and, so far, only) binding recommendations, requiring the Crown to return commercial properties worth some $3.2 million (and making further non-binding recommendations worth a further $2.9 million). The Crown and claimants had 90 days to reach agreement before the compulsory provisions took effect. In the event, a negotiated settlement was agreed on and the binding orders were never finalised.

Ngati Turangitukua received a compensation package valued at $5 million, along with an apology from the Crown. Their mana had at last been acknowledged and a platform laid for the future development of the tangata whenua of Turangi.

Comments

Post a Comment